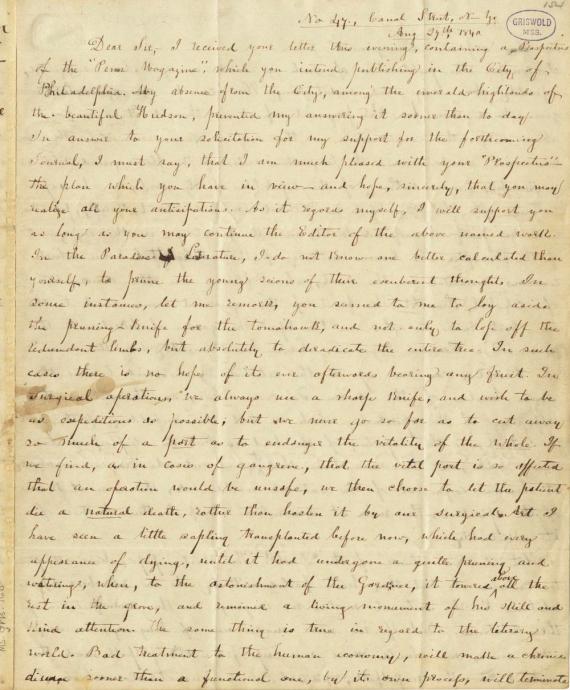

THOMAS H. CHIVERS to EDGAR ALLAN POE, Autographed Letter, August 27, 1840

No. 47, Canal Street, N.Y.,

August 27th, 1840.

Dear Sir, — I received your letter this evening, containing a Prospectus of the “Penn Magazine,” which you intend publishing in the City of Philadelphia. My absence from, the City, among the emerald highlands of the beautiful Hudson, prevented my answering it sooner than to-day. In answer to your solicitation for my support for the forthcoming Journal, I must say that I am much pleased with your “Prospectus” — the plan which you have in view — and hope sincerely that you may realize all your anticipations. As it regards myself, I will support you as long as you may continue the Editor of the above-named work. In the Paradise of Literature, I do not know one better calculated than yourself to prune the young scions of their exuberant thoughts. In some instances, let me remark, you seemed to me to lay aside the pruning-knife for the tomahawk, and not only to lop off the redundant limbs, but absolutely to eradicate the entire tree. In such cases there is no hope of its afterwards bearing any fruit. In surgical operations we always use a sharp knife, and wish to be as expeditious as possible; but we never go so far as to cut away so much of a part as to endanger the vitality of the whole. If we find, as in cases of gangrene, that the vital part is so affected that an operation would be unsafe, we then choose to let the patient die a natural death, rather than hasten it by our surgical art. I have seen a little sapling transplanted before now, which had every appearance of dying until it had undergone a gentle pruning and watering, when, to the astonishment of the gardener, it towered above all the rest in the grove, and remained a living monument of his skill and kind attention. The same thing is true in regard to the literary world. Bad treatment to the human economy will make a chronic disease sooner than a functional one, [[and]] by its own process, will terminate in organic derangement.