We grant him high qualities, but deny him the Future.

Poe, “Review of [Longfellow’s] Hyperion,”

1839

In Hexameter sings serenely a Harvard

Professor;

In Pentameter him damns censorious Poe.

Longfellow, Journal, February 24, 1847

Poe also accused Longfellow of failing to understand what poetry should do for readers. Rather than preaching, instead of arguing for causes and values, literature should be delightful. As early as 1831, Poe arrived at the position that would make him a foundational figure in the development of popular culture: “He who pleases,” he wrote, “is of more importance to his fellow men than he who instructs.” Because Longfellow was backward looking, and especially because he was a leading supporter of what Poe called “the heresy of the didactic,” Poe predicted that Longfellow’s reputation would not endure, that he would have no place “in the future.”

Longfellow’s friends—including James Russell Lowell and Oliver Wendell Holmes, both members of the Saturday Club that met in the Parker House hotel starting in the mid-1850s—sprang to Longfellow’s defense. In his “Fable for Critics” (1848) Lowell addressed Poe directly:

Who–but hey-day! What’s this? Messieurs Mathews and Poe,

You mustn’t fling mud-balls at Longfellow so, …

Deduct all you can that still keeps you at bay,

Why, he’ll live till men weary of Collins and Gray.

Holmes published “Our Dead Singer” in the June 1882 issue of the Atlantic Monthly. In it, he expressed both grief and conviction:

Oh, for our vanished Orpheus once again!

The shadowy silence hears us call in vain!

His lips are hushed; his song shall never die.

In an introductory note to this poem, the Atlantic editors recalled that, “In America, multitudes of children, in city and village, had just given [Longfellow] the honor of their voices upon the celebration of his seventy-fifth birthday, and the memory of a poet is secure which rests in the praise of children.”

In an introductory note to this poem, the Atlantic editors recalled that, “In America, multitudes of children, in city and village, had just given [Longfellow] the honor of their voices upon the celebration of his seventy-fifth birthday, and the memory of a poet is secure which rests in the praise of children.”

Longfellow’s obituaries also tended to proclaim that his place in United States literature was secure. But Poe was right. Though for generations Longfellow’s poems were memorized and recited in schoolrooms and included in anthologies, enthusiasm for and interest in him declined throughout the 20th century.

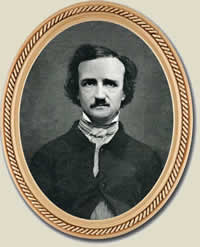

From the start of his career as a book reviewer and literary theorist, Edgar Allan Poe (1809–49) defined himself in opposition to Boston’s literary elite. Rejecting what he saw as regional pride, a lack of originality, and especially didacticism, Poe railed against the writers and editors he derisively labeled “Frog-Pondians”:

The Bostonians are very well in their way [Poe wrote in 1845]. Their hotels are bad. Their pumpkin pies are delicious. Their poetry is not so good. Their common is no common thing — and the duck-pond might answer — if its answer could be heard for the frogs. But with all these good qualities the Bostonians have no soul.

The Bostonians are very well in their way [Poe wrote in 1845]. Their hotels are bad. Their pumpkin pies are delicious. Their poetry is not so good. Their common is no common thing — and the duck-pond might answer — if its answer could be heard for the frogs. But with all these good qualities the Bostonians have no soul.

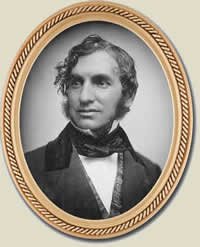

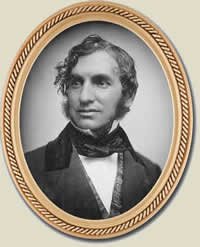

Called the “Tomahawk Man” for the severity of his reviews, Poe often targeted the beloved poet Henry Wadsworth Longfellow (1807–82). In one scathing review after another, Poe demonstrated that Longfellow’s poems were derivative, familiar, and generally plagiarized.

Poe also accused Longfellow of failing to understand what poetry should do for readers. Rather than preaching, instead of arguing for causes and values, literature should be delightful. As early as 1831, Poe arrived at the position that would make him a foundational figure in the development of popular culture: “He who pleases,” he wrote, “is of more importance to his fellow men than he who instructs.” Because Longfellow was backward looking, and especially because he was a leading supporter of what Poe called “the heresy of the didactic,” Poe predicted that Longfellow’s reputation would not endure, that he would have no place “in the future.”

Longfellow’s friends—including James Russell Lowell and Oliver Wendell Holmes, both members of the Saturday Club that met in the Parker House hotel starting in the mid-1850s—sprang to Longfellow’s defense. In his “Fable for Critics” (1848) Lowell addressed Poe directly:

Who–but hey-day! What’s this? Messieurs Mathews and Poe,

You mustn’t fling mud-balls at Longfellow so, …

Deduct all you can that still keeps you at bay,

Why, he’ll live till men weary of Collins and Gray.

Holmes published “Our Dead Singer” in the June 1882 issue of the Atlantic Monthly. In it, he expressed both grief and conviction:

Oh, for our vanished Orpheus once again!

The shadowy silence hears us call in vain!

His lips are hushed; his song shall never die.

In an introductory note to this poem, the Atlantic editors recalled that, “In America, multitudes of children, in city and village, had just given [Longfellow] the honor of their voices upon the celebration of his seventy-fifth birthday, and the memory of a poet is secure which rests in the praise of children.”

In an introductory note to this poem, the Atlantic editors recalled that, “In America, multitudes of children, in city and village, had just given [Longfellow] the honor of their voices upon the celebration of his seventy-fifth birthday, and the memory of a poet is secure which rests in the praise of children.”

Longfellow’s obituaries also tended to proclaim that his place in United States literature was secure. But Poe was right. Though for generations Longfellow’s poems were memorized and recited in schoolrooms and included in anthologies, enthusiasm for and interest in him declined throughout the 20th century.